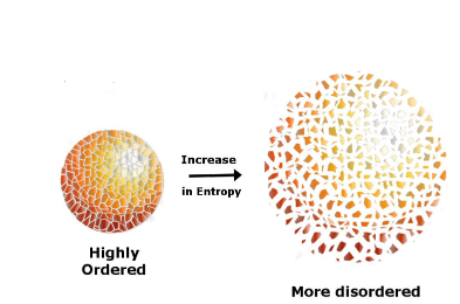

"Entropy" is an interesting word. It has two meaty definitions, the first is very scientific and the second is very interesting. Here is the official definition from Webster's:

1. A thermodynamic quantity representing the

unavailability of a system's thermal energy for conversion into mechanical

work, often interpreted as the degree of disorder or randomness in the system.

"The second law of

thermodynamics says that entropy always increases with time."

2. Lack of order or predictability; gradual decline

into disorder.

"A marketplace where entropy

reigns supreme."

The first definition is kind of scary. "Entropy always

increases" means that eventually the Universe will suffer heat death, when

everything stops, or so some of my engineering-degreed colleagues tell me. But

that will be many billions of years from now, so I think we can safely focus on

the second definition today.

Entropy as a lack of order, a lack of predictability, a gradual decline into disorder. In the realm of portfolio management, that is scary enough.

When I started digging into this topic, it really struck me that

I have been watching, advising, and discussing portfolio management for 25

years and I have seen this sort of entropy all the time. It's not a decline

into chaos, but rather it is a slow decline into a lack of discipline.

Portfolio management should be an extremely disciplined process. It's not a

random walk theory whereby we just buy a little bit of everything with the hope

that nothing blows up too badly. Sadly, as I watch portfolio managers across the

spectrum from fixed income to equities, I see this gradual decline into

disorder. When markets are fairly boring, it could become easier and easier to slip

into an entropic haze and start doing things that just don't make sense.

Remember, the easy path is towards entropy, and eventually chaos.

I think it really comes down to two very disparate

approaches. The first (and worst) is a very passionate intensity where someone

practices an approach of "diverse" sectors, an effort to ensure that there is

enough variety within the portfolio, always a having certain proportions of

certain specific sectors, under a relatively fixed policy, often written in the

distant past! The problem with this approach of managing by sector is that there

is no sector that is always a good investment. None. When we blindly and/or passionately

manage a portfolio by a prescribed percentage or allocation, those currently

good and those currently poor, we guarantee that at best we will be average. We

must be willing to that admit at any time certain sectors or groups of sectors will

be sub-optimal, and don't belong (for the moment) in our portfolio.

The second (and more difficult) path takes intensity, determination,

and process. One of the things that we have been teaching for years is the

seemingly easy, but difficult to adopt, truth that good portfolio management requires

a simple, disciplined process. We need to identify current poor risk/rewards

and eliminate them. We need to attempt to identify current good or even great

risk/rewards and acquire them. And finally, we need to try to identify good

combinations of risk/rewards—whose value can only be seen in that combination—and

execute them.

One of the things that we have been teaching for years is the seemingly easy, but difficult to adopt, truth that good portfolio management requires a simple, disciplined process. We need to identify current poor risk/rewards and eliminate them. We need to attempt to identify current good or even great risk/rewards and acquire them. And finally, we need to try to identify good combinations of risk/rewards—whose value can only be seen in that combination—and execute them.

Let's focus on the first point. When we can identify poor

risk/rewards, we need to eliminate them from our portfolio. This can be painful,

because as the portfolio manager this often means that you probably originally

acquired this "poor" risk/reward. That means that you either made a bad

decision originally, or that something has changed. This may also mean that you

need to realize a loss, which is never pleasant. Therefore, it becomes so important to be able

to articulate why the investment is sub-optimal. This is where the idea of

intensity, determination, and process kicks in. It takes effort to show people

why an investment (potentially your prior decision) has become a less optimal

risk reward decision going forward. Initially, it feels scary and a

little intimidating, but once you have fully established this more difficult

process on an ongoing basis, the payoff can be tremendous. As I mentioned last

week, it does take some bravery to admit a mistake, but in the long-term it usually

pays huge dividends.

Think about the alternative, which we discussed above. Being

extremely passionate and having a lot of intensity in following a recipe—even

when it is suboptimal—is the much easier path. You can ignore the value of past

decisions, if they followed the allocation requirements, and so be passionate

in saying you "did the right thing." It's a strange conundrum but being

passionate in defense of poor choices can be the easier path. Being humble and

contrite about a bad decision is so much more impactful. People will remember

it and, as Screwtape said in his toast which I discussed last week: "I'm as

good as you," doesn't work. Your peers will know that you will let them know when

you've made a bad decision. Wow. Powerful character trait, too.

As Shakespeare expressed in his classic play Hamlet, "the

Lady doth protest too much, methinks."

Going back to the title: entropy. We must remember that eventually markets will move to a more disordered reality.

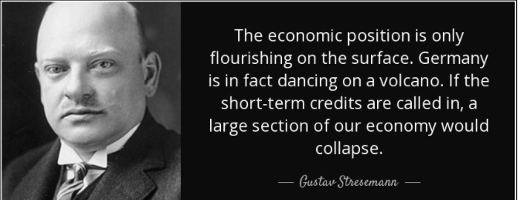

Let's go way back to the 1920s. The market was roaring at

that time. Inflation was starting to sneak into the equation and several of the

then-dominant economies, namely France and Germany, left the gold standard. The

market was soaring and had reached new highs. The "Great" War had ended, but as

Gustav Stresemann (the German Foreign Minister) said at a speech to the League

of Nations in 1929, "Germany is, in fact dancing on the edge of a volcano."

Shortly thereafter, the stock market—and financial markets in genera—absolutely

collapsed. Germany, France, and Britain lost nearly 50% of their gold reserves

within 12 months largely due to the U.S. calling in their short-term loans. The

problem was that all these governments had been borrowing like crazy and suddenly

credit disappeared.

The volcano exploded and chaos ensued. And the U.S. had it

better than most! Yet, one of every seven U.S. banks failed within 24

months.

Entropy will increase, sometimes slowly, sometimes more

rapidly, but it always will increase. A disciplined approach is so critical in times

when this becomes apparent to all as pride and passionate defensiveness will

not get us through them.

Final, final thought: I recently discovered Blue Diamond

Bold Salt 'n Vinegar Almonds. They are incredibly addictive and very tasty…give

'em a try.

Be sure to fill out the form below to subscribe to my weekly blog.