Sometimes, you get lucky. A couple of weeks ago in my post

"Talking Bubble Heads," I briefly discussed the South Sea Bubble. That article

had sent me down a path of research and intrigue that I hadn't expected. Candidly,

I had never even heard of the South Sea Bubble before I started doing the

research for that post. That article inspired quite a bit of feedback, which is

probably not that surprising given the current experience. After all, has

anyone noticed the NASDAQ lately?

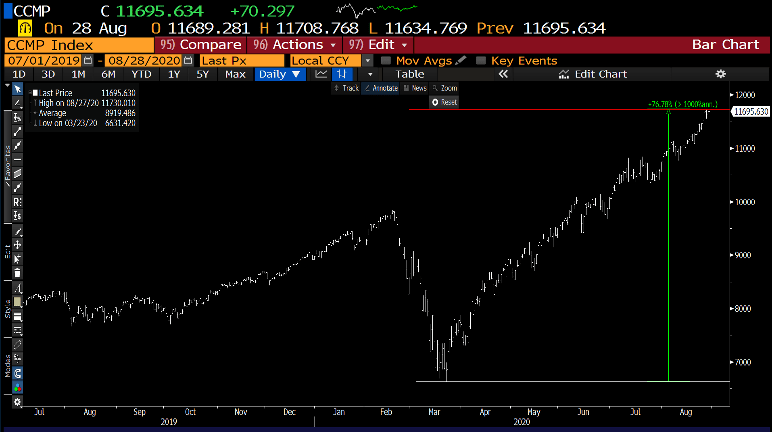

The index has risen from a low of 6,631 on March 23rd

to 11,730 on August 28th. Think about that for a minute. It's almost

a 77% increase in the last five months. Some would say the craziest five months

in the last 100 or so years. I, for one, cannot think of anything crazier that

has happened. Maybe the moon landing, but I consider that a positive. Very few

positive things have occurred in 2020. I'm pretty sure all of the new college

freshmen out there would agree with me!

So back to luck (or maybe it's coincidence). Typically, I

will research something pretty thoroughly to prepare a post, and shortly

thereafter, that research will fade into the background of my memory. That was again

true of the South Sea Bubble research I mentioned above. Then, as I was reading

the Wall Street Journal this weekend

(author's note: The Wall Street

Journal weekend edition is

my favorite read of the whole week!), I spotted an excellent piece on the last

page of the Review section, written by Jason Zweig. It was a review of a picture

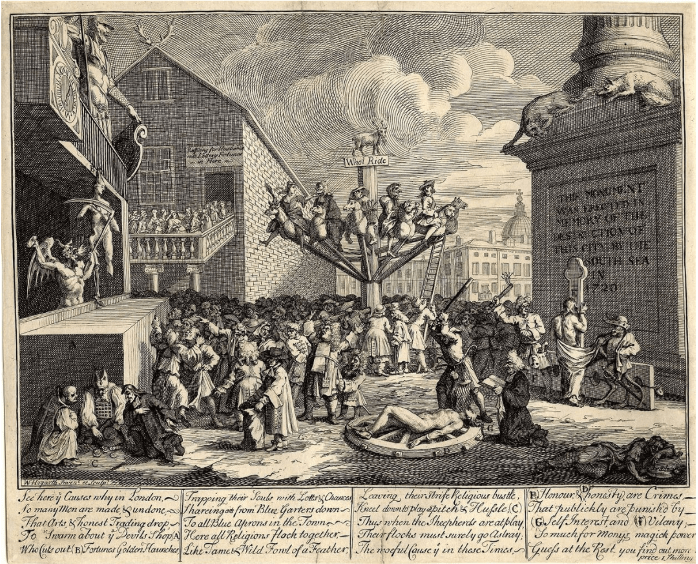

entitled "Etching of the South Sea Bubble - Born of Boom and Bust." I'm

definitely not too proud to borrow some of the amazing insights that can be

taken from his review of this piece of art. I actually couldn't believe the

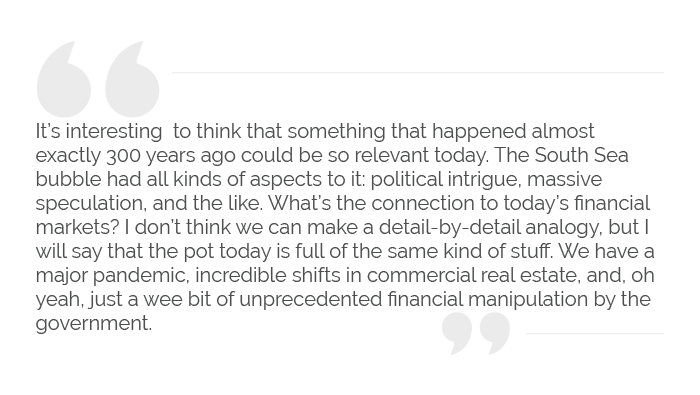

timing. It's interesting to think that something that happened almost exactly

300 years ago could be so relevant today. Here is the picture:

Now, as you may recall from my earlier post, the South Sea

bubble had all kinds of aspects to it: political intrigue, massive speculation,

and the like. What I did not realize was that it also involved a lot of debt.

It seems unbelievable but essentially the South Sea Company was issued a total

monopoly on slave trade and "potentially" lucrative trade with South America.

It was also advertised as an almost certain way to get massive amounts of gold

from the same. Unfortunately, at the time, England was at war with Spain and

actually had very limited access to the important ports they would need to access.

But all of this was brushed aside in the mania. In exchange for this monopoly,

the company accepted massive amounts of government debt that was supposed to be

paid back through a 6% dividend paid directly from the government, and convert

it to company stock. What could go wrong?

Sorry to delve back into that story, but a little background

was needed. This was one of the worst financial disasters in the history of

Great Britain. In fact, William Hogarth—the creator of the etching above—suggested

that the damage was literally irreversible: England would never recover. Of

course in hindsight, we know that England not only recovered but also became

one of the great financial centers the world has ever known.

So, what do I find so interesting about this etching? It

parallels today.

As Mr. Zweig describes in his article:

"Hogarth lays out his fraught tale using

a mixture of symbol and allegory, much of it helpfully explained in the text he

added at the bottom. On the left, Satan has turned Guildhall, the

administrative seat of London's government, into a meat market. He hacks the

goddess Fortune to pieces and heaves chunks of her bloody flesh to the mob. At

the edge of the crowd, a dwarf and a liveried footman pick the pockets of a

schoolmaster. Some scholars have argued that the dwarf is [Alexander] Pope, who

stood 4-foot-6. Next to the monument, a figure of "Vilany" (Villainy) flogs

"Honour" as an elegantly clad monkey—long a symbol of folly and greed—bares

Honour's back for the lashing. Nearby "Honesty," lashed to the wagon wheel, is

about to be bludgeoned by 'Self-Interest'."

Kind of graphic, awful busy, but very powerful. You may recall that in my first piece on this topic, I mentioned that this company and bubble occasioned the emergence of this example of what today we call SPACs, or Special Purpose Acquisition Companies. In 1720, they were trying to sell people on, among other projects, the idea of square cannonballs.

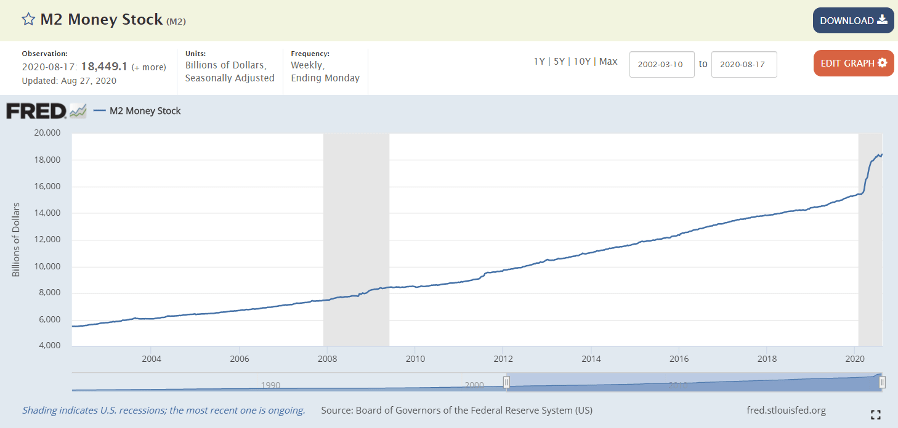

What's the connection to today's financial markets? I don't think we can make a detail-by-detail analogy, but I will say that the pot today is full of the same kind of stuff. We have a major pandemic, incredible shifts in commercial real estate, and, oh yeah, just a wee bit of unprecedented financial manipulation by the government. We have somehow managed to issue an almost unlimited amount of debt only to buy it right back up via the Fed. Money supply has skyrocketed from roughly 15 trillion to almost 19 trillion in just six months. The velocity of money is collapsing to the lowest level ever recorded.

And SPACs? Enough said!

Thankfully, we are not at war with Spain, so access to the

South Sea ports are not currently a problem.China, however, is not exactly a tranquil silk watercolor scene, either.

What will our relationship be with them over the next three, five, or ten

years? It's a pretty important factor.

I learned something else surprising in Mr. Zweig's review.

Leading up to the bubble bursting in 1720, there were "stock jobbers" who would

lend you their shares for a few days or a few hours—for a fee.This, of course, enabled all kinds of scams

and even more manic behavior. It allowed even the shoeshine boys to play in

this great and hectic game…which somehow reminds me of the Robinhood craze we

are seeing today: Thousands of millennials now trade shares—even fractions of

shares—on this platform. Here is a link to

the 100 most popularly traded stocks at Robinhood. I'm quite sure there is a

ton of detailed research going into these trades…not.

So, am I saying we are in a bubble or are repeating some

kind of epic failure pattern? Not at all. I'm just observing. As the great Joe

Madden, former manager of the Cubs, always said: "Just try not to suck!"

But none of us know the future, and none of us ever will.

Final, final thought: My inspiration for this article came

from page C14 of The Weekend Journal. Never stop reading.

Be sure to fill out the form below to subscribe to my weekly blog.