Ok, let's be really honest with ourselves for a moment...how

many of us know where Slovenia is located? I had a general idea but ended up

having to Google it to really pinpoint it. It turns out Slovenia borders

northern Italy and is just across the Adriatic Sea from Venice. It is a country

of just over two million people and a member of the Eurozone. There is a history

of war and conflict in this region over the millennia. It looks like a lovely

country.

In fact, learning about Slovenia has me thinking I might

want to visit. Here, I'll share a link

to the tourist bureau so you can decide if you'd like to, too.

By now, you have probably noticed this blog wanders a bit in

its observations. Unless I am transitioning to a career in a travel agency, why

the heck am I bringing up Slovenia, charming as it may be?

Because today, Slovenia—the Slovenia most of us probably

couldn't exactly locate on a map—hit a very interesting milestone: Their 10-year

note yield just hit 0%. Yes, you can purchase the sovereign Slovenian 10-year

7/8% coupon note for a price of roughly $108.87 (though this is not a

recommendation, by the way).

By my rough count, there are now 15 countries within the

Euro-zone whose 10-year yields are at 0% or below. At least the United Kingdom is

paying something positive, a full 0.10%, which investors can enjoy for 10 long

years. Let's put some numbers to that because thinking in terms of percentages

can be a little discombobulating. If you invest 1 million dollars into a 10-year

maturity UK sovereign bond, you would receive a handsome $500 every six months.

Let that sink in.

A quote I saw in Bloomberg this morning really caught my

attention:

"Investors are desperately trying to find yield somewhere," said Jan von Gerich, chief strategist at Nordea Bank Abp. "At times there are reminders of the risks involved, but it seems in the current environment such news is merely a temporary setback in the bigger picture of contracting risk premia."

The phrase that

made me feel very nervous was, "at times there are reminders of the risks

involved"! Reminders?

What the heck? People are buying bonds—sovereign bonds, and domestic to them—with

literally no income. I have always believed that there are two reasons why I

would ever want to put my money at risk: income or capital appreciation (and

preferably both!). If I invest in something for the next 10 years that is guaranteed

to have NO INCOME, I better be really confident that there will be some

potential price appreciation.

This doesn't get

better with shorter maturities. It gets worse. Here is a table of 5-year

yields across Europe—and yes, you are reading that correctly: the German 5-year

note was at -0.68% when I grabbed this data.

Back to the quote that caught my attention from Mr. Von

Gerich: Has the idea of risk escaped all of us?

Almost by definition, since it is receiving no income, the market is

betting that prices will continue to go up (and therefore that yields will go

down, even further negative). The German note, for example, is a 0% coupon bond

trading at a price of $103.612. I do understand that there are other forces at

play here, most notably central banks pumping unbelievable amounts of money

into the bond markets, but they are not the only buyers.

What about the risk no one seems to be reminded of? What if

German rates were to "skyrocket" up to 1%? Does that seem crazy or impossible? An

outlandish rate? I don't think so, sounds like not-to-distant experience,

actually. If that happened, the price on the 0% coupon notes would drop to

approximately $95, or by just over 8%. That represents an $80,000 loss per

million for the investor. Have I mentioned lately that there is no income being

earned from this security?

How can we possibly invest in the fixed income markets

without measuring risk? It doesn't make any sense. So far in my 25 years in the

fixed income arena, risk has always been paramount. Most participants lived in

fear of an aggressive rise in rates, especially depository institutions.

Duration (an attempt to measure price risk statistically) has almost always

been a major determinant of the investment decision.

Today, it feels like most people live in fear of rates going

down. This fear is indeed justified. We all must have a plan for that

environment—it clearly could happen. Policies like yield curve controls or negative

Fed Funds rates are being actively discussed at the Fed and by the chatter

heads on CNBC (see my previous post for more on that topic). When the investment

shows discuss rates these days, they only discuss one scenario: rates

down.

In my days of yore as an option trader at the Chicago

Mercantile Exchange, we described phenomena like this with the term "skew." In

other words, when everyone is leaning one way, a market develops a skew towards

that direction. To us, it was always a signal that something was out of whack.

Following the mini-crashes of the late '80s, the skew was always to the

downside. People always sweated out October because that's when the two major

stock crashes occurred—and that fear turned into short futures positions on the

exchange. Unfortunately for them, following the skew turned their premiums to

dust, given that we actually entered the longest, greatest bull market of all

time.

Instead of following the skew, how should we approach the

market? My fellow instructor at our investing classes, Chris Carney, frames it

really well with the acronym TMI. Not the usual "too much information".

Instead, Chris says that when we invest, we need to take into account time, money,

and interest scenarios—TMI. It's such a simple idea, but it's not always super

easy to quantify. When dealing with a sovereign, agency, municipal, or highly-rated

corporate debt, it's not that complicated but once you start considering securities

with variable cash flows, it can get tricky. Not impossible, just a lot more

complicated. The details of that discipline are beyond what I can cover in a

blog post, but the point I hope you'll hold on to that we cannot ignore the

risk component of our investment decisions. Right now, we have these huge elephants,

known as Central Banks, buying up all the assets in the system, in addition to

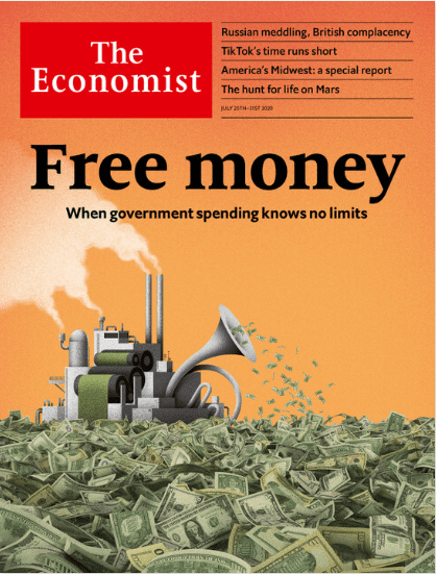

pumping cash into their economies. This weekend's cover of "The Economist"

succinctly summarized this behavior as "Free Money"! The tag line is really important as well:

"When government spending knows no limits".

This ride will eventually end—it has to, and it will be painful. On that

day, there will be risk, which means that today, there is risk, recognized or

not. When risk is recognized, prices will go down. We just don't know when the

fun ends: one year, two years, more?

I'm not suggesting we sit the market out, but when we invest, let's invest like we remember something called risk.

In the meantime, check out that Slovenian website I linked—it looks like a lovely place to visit. As an American, they probably won't let you in at the moment, but maybe you can work Lake Bled into your 2021 vacation plans!

Final, final thought—I went to an old-fashioned, pre-COVID wedding this weekend. It actually felt normal. We need more of that. Congrats to the new Mr. & Mrs. Greene!