I want you to imagine a world in which the government in your country enforces strict limits on the amount a lender can charge for a loan.

Let's call it 13% for a round number. Continue down this imaginary path further

and imagine banking in this land operates without any of the agency guarantees

that we enjoy in the United States: no FDIC, no FFCB, no GNMA, no FNMA, no

Freddie Mac. Let that sink in for a quick minute. Now, I want you to add a few

more variables into the mix. In this land, almost no one can qualify for a loan

because they have very little or no savings. Most people have no

collateral. Their economic condition is often

at the mercy of the vagaries of the weather and "luck". The idea of a mortgage

greater than 10 years is never even considered and down payment expectations

are in the 30% range.

A place like that exists, today.

That place is most of Africa. And what I am describing

specifically is the relatively advanced financial system in Kenya. Last week I

made my fourth trip to Africa with a group called Partners Worldwide. You can

check out their website here. Their

mission is to work with smaller businesses and financial organizations in third

world countries, teaching them excellent business practices. Without going into

it too much, it has profoundly changed the way I think about banking. It has

also made me profoundly grateful for the incredible systems we have available

to us. I went to Kenya to work with MFIs (Micro Finance Institutions)

specifically around the area of Small/Medium enterprises (SMEs). It has been a

wild ride and I have come to appreciate just how valuable the banking systems in

the United States and most of Europe really are. Some of the MFIs that I have

worked with are not allowed to take deposits…even if they had customers able to

deposit. This right is left solely to the huge banks, and they pay very close

to 0% on those deposits. The larger banks usually set a minimum loan amount

well above the operating needs of any medium to small sized business, because

they are frankly risky. This leaves many businesses that need to find 50-100k

dollar loans outside of what we would consider the normal banking arena. In my

experience during normal times, these businesses have repayment rates in the

95%+ range, even as they pay what would seem to us to be exorbitant interest

rates. However, despite that kind of "normal" performance, African nations have

no shortage of political risk—just check out Somalia! Without the help of MFIs, these smaller

businesses are forced to deal with what I can only call loan sharking

operations typically charging between 5-7% per month! Obviously, they operate

outside the legal 13% limit.

The purpose of this trip was to help these smaller MFI

operations by creating a fund to buy their loans. My overly simplistic explanation was that if

they are charging 13%, this fund could buy the loans, allowing the originators

to keep 7% for servicing, while we would grow our fund pool with the remainder.

It's a longer story than that, but given your familiarity with the U.S. context,

you probably get the idea. It happens every single day in America, where most

banks or credit unions simply log into their Fannie Mae desktop and sell their

loans with the click of the button.

The idea of selling loans had never been discussed in Kenya before,

at least as far as I have been able to determine. I met with big banks, small

banks, MFI's, SACCOs (the African version of Credit Unions), regulators, and

industry experts. No one had ever contemplated the idea of selling a loan. It is

such a foreign concept that they could hardly comprehend what that meant. Think

about that. Loans across the United States (and the entire developed world) are

actively traded, securitized, and sold. All day and every day. If I'm honest

with myself, I sometimes forget how powerful those simple actions are. It

clears balance sheets, helps mitigate concentration risk, makes credit more

accessible to more people, the list goes on and on. It has transformed banking

in our country, and through it home ownership, small business success, and more.

Banking in the U.S. has created a wealth machine for its citizens. Has it ever

been abused? Of course.

Think of the movie It's a Wonderful Life. It is

almost Christmas after all but recall the scene where Uncle Billy has caused a

run on the building and loan because he misplaced some of the cash, and the

mean old Mr. Potter wants it to fail. The visiting bank regulator wants to shut

them down: the depositors are in an uproar and George Bailey (Jimmy Stewart)

wishes he had never been born. This is what banking in an economy with no

support systems feels like every day. There is literally no access to capital.

Nor credit at a reasonable rate. No leverage. No borrowings.

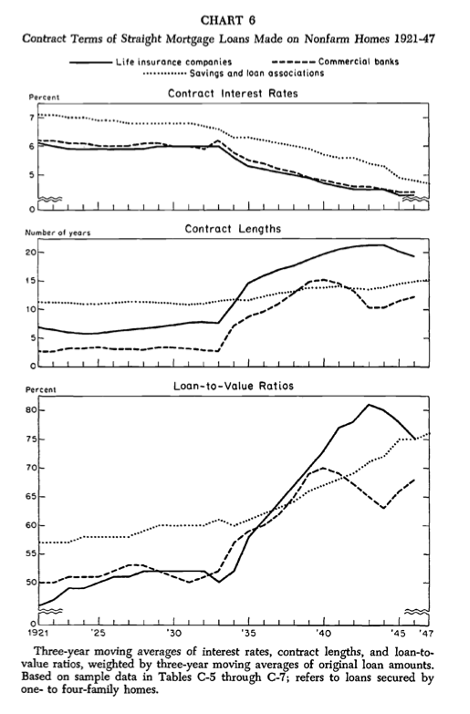

Let's go back up to the first paragraph describing an "unusual" existing mortgage market. 10-year max terms at 13% with 30% down. What do you think home ownership rates are in a place like that? I would love to find some mortgage stats from the 1900-1920 era, but the earliest data I could find was in the archives of the National Bureau of Economic Research. The graphic below starts in 1921 and reflects mortgage rates, contract lengths, and LTVs during George Bailey's era.

I've also learned that these were generally non-amortizing

balloon structures that were generally balloon loans and rolled over every 5-7

years. In the early part of the graph, the rates and terms are not very

different from what I see in Africa today. Suffice it to say that in the pre-agency

era, banking was very different. Massive safes with lots of cool features sat

in every little country bank. If weather took out local crops, foreclosures skyrocketed,

and people lost everything. The modern era of banking—let's peg that to the

establishment of the FFCB (March 27, 1933)—has radically changed all of that.

We take it for granted.

So, what is the real point of this post?

Bear with me for a minute because I think this is important. Among African bankers, I saw the same sort of reaction to ideas we find commonplace, like selling loans, as I often see among U.S. bankers when they are presented an idea that is new for them. "It can't be done" or "We just don't do that here."

Of course, our systems and ideas have advanced beyond the

simple idea of selling a motorcycle or car loan into a pool so we can relend the

funds. Many complex ideas are created every day in the U.S. financial system,

and some of them should be avoided, but some are extremely powerful. In some

ways, smaller American banks and credit unions face challenges similar to those

of their much smaller cousins in Africa and the rest of the developing world.

The bigger banks don't really care if you survive or fade into the ether. They

really don't. They have access to things that you do not have. They have bigger

credit lines, more and effectively cheaper technology, and a myriad of other

advantages. I talked a lot about that in a prior post.

So, what's the point? For American banks sounding like my

Kenyan friends and asking about new ideas, I give them the same response: "Tell

me why you can't." I'm guessing there were similar conversations when FFCB and

FNMA first started buying loans. Change is hard. I wonder how long many banks

who were unwilling to adapt to this opportunity remained independent.

The banking industry has transformed America in very good

ways, of that I have no doubt—this trip cemented that in my mind. But we do

need to remain open to new ideas. I'm not trying to say every innovation will

be as transformational as FFCB, FNMA, GNMA and the FHLBs, but we do need

constantly ask ourselves that simple little question— "Tell me why we can't?"

This trip inspired so many thoughts, far more than I can

cover in a blog post. I would be happy to discuss my trip, or the ideas it

generated, at length. Shoot me an e-mail or give me a ring.

Final, final thought: I think I had the best Indian food

ever at a restaurant in London called Tamarind.

They don't mess around and the food was so good. If you get the chance

to go, do it!

Fill out the form below to subscribe to my weekly blog.

The information, analysis, guidance and opinions expressed herein are for general and educational purposes only and are not intended to constitute legal, tax, securities or investment advice or a recommended course of action in any given situation. Information obtained from third party resources are believed to be reliable but not guaranteed. All opinions and views constitute our judgments as of the date of writing and are subject to change at any time without notice.