Shanghai is a city of nearly 25 million people, and they

have been in an iron-clad lockdown now for almost six weeks now. This is not a stay-at-home

order like we experienced in the United States, where guidelines have been

loosening—wearing a mask on an airplane has even become optional for us. Alternatively,

in Shanghai, the government has implemented measures such as installing

electronic door alarms on the homes of those who have tested positive for COVID-19,

forcibly removing people from their homes while leaving their pets behind and leaving

the doors to their homes open to permit industrial-style sanitation. They have

bussed people who have tested negative more than 100 miles from their

homes, just because they had close contact with a positive case. Freshly built chain

link fences are suddenly popping up around people's houses and apartments, locking

residents in. They are disinfecting the street surfaces with lime! How many

people are contracting COVID-19 by walking on the streets? The lime they are

using to "cleanse" all the outdoor areas is extremely alkaline and will likely

mess up local waterways for years to come. The local authorities have been told

to stop the spread at all costs, and that is what they are trying to do.

Some in the locked-down areas of the city are struggling to

get food and medical supplies. There are heart-wrenching videos of citizens

yelling out at night, begging for anyone who might have fever medication for

their family members. Commonplace surgeries and lifesaving medical services are

not available. Out of the 25 million people in Shanghai, only about 87 people

have died due directly to COVID-19. Somewhere around 4,000 have had symptoms

(most of them from the elderly population, according to Bloomberg. Think about that

number for a minute: out of 25 million people, 0.00034% have died. Most cases

are asymptomatic. This is all due to the Omicron BA-2 strain which is easily transmissible.

Scientists generally believe it to be more transmissible than the measles, the

common cold, and even the flu. Thankfully, it is not nearly as virulent as

earlier COVID-19 strains.

All of this is happening because the Chinese government has

issued a zero COVID-19 policy. Unfortunately, just this week, some cases have

now been popping up in Beijing, and the markets and others fear that the

dystopian policies in force in Shanghai might soon be enacted in Beijing. The

local population is already waiting in long lines to buy as many groceries and

supplies as they can get their hands on, while they still can.

The reality is that the Omicron BA.2 variant, according to

the research I have been able to do, is not stoppable. You can put as many

people in the streets with hazmat suits as you like, lime-dust as many streets and

"disinfect" as many buildings as you want, but you will not be able to stop it.

Nonetheless, Beijing is preparing to institute similar

measures. They have had a total of 70 cases since last Friday and are now

planning to test every single person in Beijing three times each over the next ten

days. That is something like 80 million tests, a staggering number.

So, what in the world can this all have to do with bonds and

investing?

It is connected in that in both the Chinese zero COVID-19 policy,

and many investment approaches, spurious and misleading statistics are leaned

upon in an attempt to perfectly measure risk. Those in investing might fail

almost as miserably as the Chinese government has. I want to look at three of

the most obvious and often misleading statistics but will reserve the right to highlight

more in a future post. Let's start with the big three:

Yield, Duration, and Average Life

Let's start with the granddaddy of all single-statistic

parameters: yield.

I think it is helpful to go back to the origins of the term

yield, which comes from farming. According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary,

when yield is used as a verb it means to produce or provide. In the financial

context, it has become a shortcut for how much income I should/might receive

from an investment. When you start digging into the way that Bloomberg and

other financial calculators try to measure this value, the waters start to get

really muddy really fast. From Bloomberg, the following caveat is in their

definition:

"While there are a lot of

variations for calculating the different kinds of yields, a lot of liberty is

enjoyed by the companies, issuers and fund managers to calculate, report and

advertise the yield value as per their own conventions"

Furthermore, Bloomberg suggests the entire calculation of yield

as null and void once you start looking at floating coupons derived from an

index, since we cannot know the future levels of the index. They should offer

a similar caveat for any security with unknown future cashflows.

Is it really that complicated? The street would love for us

to believe that it is simple. It helps to sell securities and is used as a

talking point in almost every single sale of a fixed income security. In the

most common presentation of a mortgage backed (or asset backed) security, yield

is actually calculated out to the fourth decimal place. The interesting thing

that anyone familiar with the math would confirm is that this calculation is

almost certainly wrong from the outset. Wrong. Dead wrong. Known to be wrong in

the sense that it is almost certainly never going to play out to that fourth

decimal—or even to the first—in reality.

Here's the catch. We cannot even make the yield calculation

work if we do not know the exact cashflow and re-investment rate of every

single payment. In the case of a simple 15-year mortgage pool, that means we

would need correctly predict exactly what the payment stream is for every

single future month - 180 months in a row. It's just not possible.

If you think I am overstating this, do a little research of

your own. What you will find is that any serious discussion of yield on a

security (or loan!) in which the future cashflows are not certain is a very

vague and almost meaningless discussion. And yet we all engage in it.

Duration

If possible, the use of duration as an investing

tool/measuring stick can be even more pernicious and potentially

misleading than the use of yield.

Why is it such a troublesome statistic, you may ask? I think

mostly because it is so misunderstood. In our common vernacular, the term

duration almost always means measurement of time. For example: "What is the

duration of the musical recital?" or, "The duration of the flight is around six

hours." If you go to the dictionary, you will find that duration is defined as

a time during which something occurs. In my experience teaching about fixed

income across the country for the past 25 years, that is what most investors

think duration is supposed to mean in the world of investing…and this is incorrect.

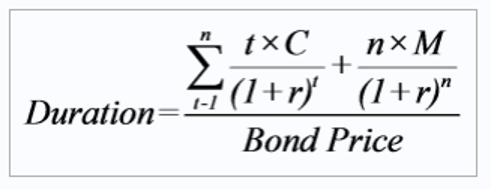

Duration and its derivatives (Effective, Modified and Macauley) in the

financial markets were designed to attempt to measure the sensitivity of the

price of a bond to an immediate change in an interest rate.

As you can see, it is a complex formula, and beyond the

scope of this little post, but there has been a tremendous amount of serious

thought on the topic. It makes sense, because we would all love to know the

price sensitivity of our portfolios to given changes in rates. Unfortunately,

most serious students of this topic acknowledge that we cannot know the future

cashflows of most securities, and even less of portfolios of securities, nor

can we know the yield curve's shape in the future, or the path rates will take

to get there. Can we approximate? Sure. Will it be correct? Probably not, and

if so, it will most likely be by coincidence.

However, this brings me back to my opening thought on how

deadly this statistic can be. Many investors will compare two or more

securities with approximately the same duration but with dramatically different

types of cashflow volatility as though it is apples to apples. But the

differences not apparent in the duration value render the calculations

irrelevant and inaccurate.

Average Life

Of the three statistics we are examining today, average life

is probably the simplest. Maybe that is why it is so often used incorrectly.

The simple physical analogy for average life is a teeter-totter (in some parts

of the country, you may call it a seesaw). When we think of teeter-totter, we

know that there is a balancing point somewhere in the middle.

Your physics professor in college referred to this as a

fulcrum. We can calculate where this

point will be using simple math. There is no need to use the present value

equation and there are no derivatives. All we need is to figure out the weights

and positions of the objects on the beam and we can find a balancing point. But

we do need accurate weights and positions.

If we can consider a pool of 15-year mortgages and think of

the principal payments as the weights, and the timing of these payments as the

positions, we can come up with a picture and process for finding this

equilibrium point and call it average life. Depending on the level of interest

rates, this number will vary, but for simplicity's sake let's call the typical

result somewhere around five years. Each month, homeowners will make a payment

on their house which is partially principal and partially interest. The

breakdown of these payments changes every month. Some people will prepay,

refinance, or change their payments based on personal situations. These changes

are unknowable to us in advance, as investors.

This is where the problem starts. As I mentioned above, the

expected average life might be five years, and so the broker-dealer community

will seize on that statistic and compare it to other five-year assets, such as

a 5-year Treasury. When they throw in the granddaddy of stats (yield) and

compare them they will almost always find that the mortgage pool's calculated

yield is higher than that of a Treasury. It will also have a lower duration.

You honestly could not find two more dissimilar securities.

The comparison makes no sense whatsoever, but it is used every single day in

the capital markets. The pool of mortgages has 180 principal payments, which

change every month, and the Treasury has only one principal payment, five years

hence.

The three statistics discussed above drive billions of dollars'

worth of fixed income decisions and they are wildly misunderstood and misused.

As a portfolio manager, developing an understanding of these widely unnoticed flaws

gives you a great advantage.

Just as the Chinese government cannot stop Omicron BA.2 by

throwing lime powder on the sidewalks and putting all their citizens under

house arrest, we cannot collectively stop the use of these statistics, but we

can understand how they are misused and deploy this knowledge to our advantage.

One thing I know for sure: single statistic parameters that do not incorporate

dynamic cashflow and interest rate scenario analysis are virtually useless.

Remember - I don't know what the future will bring, and

neither do you. Evaluate a broad, meaningful set of scenarios, and do not rely

on what the "street" gives you as being useful.

Final, final thought: I'm on a bit of an Indian food

kick…but I need some new recipes. Please send them my way!

Fill out the form below to subscribe to my weekly blog.

The information, analysis, guidance, and opinions expressed herein are for general and educational purposes only and are not intended to constitute legal, tax, securities, or investment advice or a recommended course of action in any given situation. Information obtained from third-party resources are believed to be reliable but not guaranteed. All opinions and views constitute our judgments as of the date of writing and are subject to change at any time without notice. Past performance does not guarantee future results