I came across a word the other day and, having never seen it

before, looked it up in the good old Merriam-Webster dictionary to learn that

it means: confused or meaningless talk. It got me thinking about my last post,

entitled "Cui

Bono." The connection may not be immediately clear to you, so let me

elaborate.

In "Cui Bono," I explained that in ancient Rome, one of the

important questions that any legal inquiry would ask is "Who benefits?" It

really struck me that we need to be asking that question whenever we are making

an investment decision to avoid being charmed or sold something simply because

someone is persuasive. As I thought more about this concept, I realized that

the entire language of the broker-dealer community is based on the use of terms

that would confound any person not in the industry.

As with any highly technical industry, securities industry

professionals are used to hearing things shouted at them over the phone that

would sound like total gibberish to most people. This is mostly due to the fact

that it is very common for a trader to take down a position in a security and

then sell his sales force on the merits of his position so that they will sell

it on to end customers—folks like many of you. I am constantly hearing things

marketed in terms of duration, average life, spread, tight, wide, special

situation, cheap, and one off. These terms are all fine in the short term—the

short term over which the trader expects to own the position.

Let's focus on a couple of the most confusing and over-used terms that I see on offerings all the time. Number one on the list has to be duration.

Let's focus on a couple of the most confusing and over-used

terms that I see on offerings all the time.

Number one on the list has to be duration. If I were a betting man, I

would bet that more than 50% of brokers that throw out this term do not even

really know what it means. On the surface, it would appear to mean some kind of

length of time. If you look in the dictionary, the first definition of duration

is, "the time during which

something continues." If I told my kids that the flight will have a duration of

four hours, that would pretty quickly be understood. Unfortunately, in the

world of investing, the term has nothing to do with a measurement of time. Here

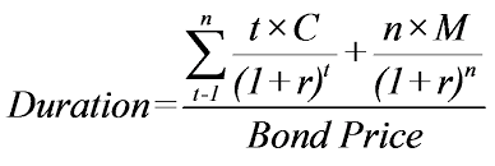

is the formula you will find for duration:

As it turns out, there are several different applications

based on adjustments to this formula: Macaulay's duration, effective duration,

modified duration, and several other more obscure versions. There are many

problems here. First and foremost is that all the formulas you will find

discussing duration assume that you know the exact cashflow schedule the

security will experience. This is possible only for bullet securities where we

do, in fact, know the cashflow schedule that is coming to us. In the case of

any amortizing security, or any security with imbedded options, we do not

have that required perfect knowledge. The reality is that the people who

developed this formula were actually attempting to measure short term price

volatility in a zero-time environment. The formula itself was never intended to

indicate anything about the length of time until maturity nor when you might

get your money back.

It's galimatias. Totally misused and misrepresented. But it's just so darn common.

At the beginning of

our educational programs, I always ask attendees to write down their definition

of average life. I do this because virtually every piece of documentation

around the sale of a pool or a CMO will highlight the average life. As you can

imagine, I get a wide range of answers. Most people will simply shrug their

shoulders and say "I don't know." And yet, so many decisions are made using

this metric. We could examine the formula to find the technical answer, but I

think I can describe it in a simpler way. It is simply the fulcrum of our

principal cashflows. I use this picture to help explain the meaning.

It turns out that it is analogous to a physics problem. How do we make the teeter-totter balance? We need to figure out the "weights" at each end as well as the length of the board, and then we can find the balancing point. With average life, the same math holds true. But, when we look at amortizing securities, we don't know the exact payment stream and therefore the advertised average life must be calculated with an assumed cashflow schedule. That schedule will be incorrect the moment an assumption is incorrect, but in the galimatias world of finance that fact is never discussed. In fact, the stark reality is that average life will change every single month as actual prepayments arrive.

Yield and spread are similarly compromised. Spread is very

simply the difference in yield between a benchmark (usually a Treasury note)

and the security we are considering. Unless the two items have the same exact cashflow,

this number quickly becomes meaningless as time goes by. Anything with

prepayments or imbedded call options cannot be accurately compared to a

Treasury whose cashflow is 100% certain and unchanging. For the vast majority

of securities that banks and credit unions buy, the cashflows cannot be known

ahead of time. Since we can't even accurately calculate yield in these cases,

just think how unrealistic it is to claim that we know the spread.

Galimatias + Hubris = Absurdity

So, how do we avoid this confusion-causing conundrum? As

Albert Einstein once said, "Everything should be made as simple as possible,

but not simpler." What did he mean by that? I believe the crux of the issue is

that he was saying that it is

desirable to keep even complex things as simple as they can

be, without losing the essence of those things. He would also have acknowledged

that some things cannot be reduced to something simpler or

they lose something of vital importance. For me, when I am making an

investment, I would like to know how much money I will actually make, over time,

and in different interest rate environments. And when I start moving into the

world of capital markets or instruments with some credit risk component, I will

have to add using a less simple representation—just as Einstein suggested.

When dealing

with an entire balance sheet of assets and liabilities, even more information

will be required, and less simple representations required. But we want to

still keep it as simple as possible for the situation. The important

thing to remember is that we should always be leaning towards making the

analysis or decision simpler—not more complex. The single statistic parameters

I discussed earlier do not help us achieve that goal.

To me, the

simplest starting point is always going to be TMI: time, money, and interest

rate scenarios. The fancy talk—galimatias—does

not help me achieve my goal.

But we want to still keep it as simple as possible for the situation. The important thing to remember is that we should always be leaning towards making the analysis or decision simpler—not more complex. The single statistic parameters I discussed earlier do not help us achieve that goal. To me, the simplest starting point is always going to be TMI: time, money, and interest rate scenarios. The fancy talk—galimatias—does not help me achieve my goal.

Final, final thought: Spring has seemingly sprung here in Illinois, which means I will soon be able to procure farm fresh vegetables like corn on the cob and fresh tomatoes (yes, I know they are fruit!). I look forward to roasted corn on the cob and a great Caprese salad…soon!

Be sure to fill out the form below to subscribe to my weekly blog.