While watching my church service on TV this weekend (how

weird it is that this has come to seem normal!), I learned a new term: kintsugi.

The direct translation of kintsugi is

"the art of healing." As the story goes, back in the 1400s, a Japanese shogun,

Ashikaga Yoshimasa, broke his favorite tea bowl. It must have meant a lot to

him because he sent it to China for repair. He got it back; the shards were laced

or stabled together with fine metal wire, and it leaked.

Dissatisfied, the shogun commanded a Japanese craftsman to

come up with a superior solution. Despite the fact that history does not record

this resourceful craftsman's name, he came up with something wonderful: He

patched the bowl together with a gold-infused lacquer. It turned out so beautifully

that it inspired a new, serious art form in Japan. To this day, there are

Kintsugi masters in Japan who teach classes, write books, and sell intentionally-broken

and repaired items. Here is an example of the craft.

I think this is beautiful. Can you imagine what the

cobbled-together version would have looked like compared to this?

So what does this art form have to do with financial

markets? Well, for starters, let's face it: a lot of things are broken right

now—markets, business models, consumer expectations. How they get put back

together might be an opportunity for some kintsugi. Or, we could end up with a cobbled-together

mess.

Remember, however, that beautiful kintsugi required a broken

element. I have seen something break in the commercial air travel business

already.

For years, the airlines struggled with a passenger boarding

process that was severely flawed. The most efficient way to load a full plane is

to start in the rear of the plane and then fill towards the front. However,

there are some "business-as-usual" problems with loading from the rear.

The seats in the rear are usually those of the

lowest-paying or least profitable customers. The core customers—the gold

level, the international elite, the grand mileage masters—they don't sit back

there. So, in the past, more inefficient boarding processes were employed to

ensure these "more valued" customers did not board to find all the space in the

overhead bins already taken. This was not a mistake, per se. These customers

are valuable and worth keeping happy, so the airlines boarded in less efficient

ways to prevent unpleasant experiences for them. They (and we) put up with a

tediously long process and eventually came to expect it.

If you've flown recently, you know that this has all

changed. With COVID-19, social distancing requirements, perhaps periods of low

usage—the system was broken by all of that and had to be put back together.

While first class and super high-status passengers still

board early, now 90% of people are boarded from the rear of the aircraft.

Overnight, the problem has been solved. My observation is that most people are

totally fine with it, and accept it as the new normal. To me, this sounds more

like kintsugi than baling twine.

I'm sure that over the past five to six months, a great many

processes broken by the shutdown have created kintsugi opportunities. Remote

working is one of the most obvious examples. I think most employers were previously

reluctant to have a majority of their staff working from home. Now, it has

become the norm for many companies, and they do not plan to ever fully revert

to the previous model. In the case of the banking industry, kintsugi seems to

be happening with both the physical branches and with customer behavior as

well. Just think how hard it used to be to get some people to use a mobile app

for their banking transactions. Maybe the younger folks got on board, but

certainly, the older crowd (define that as you will) was generally uncomfortable

with doing all of its banking online—think of payment apps and remote deposit

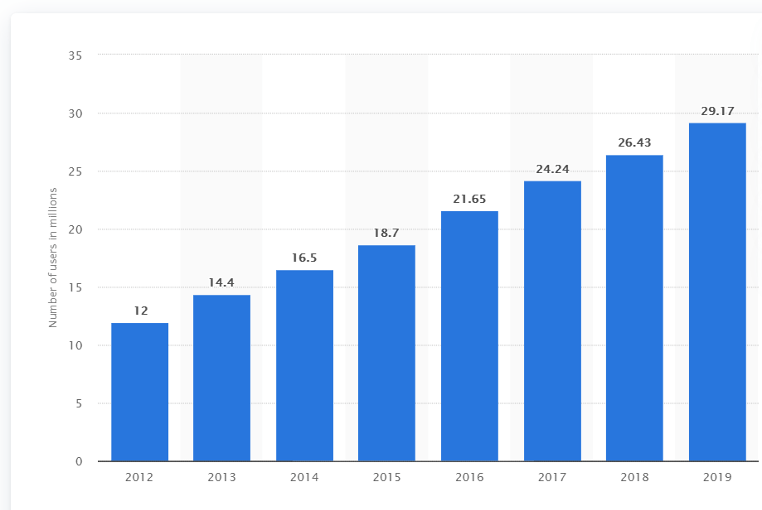

capture as prime examples. The best applicable data I could find indicated

something like 16% of deposits in 2019 were done remotely. This graphic

illustrates the number of Bank of America clients that used mobile banking from

2012 - 2019. Yes, it was steadily rising; by 2019, 29+ million people were on

their mobile platform. The numbers aren't available for 2020 yet, but I would

be willing to bet a large sum of money that the number of mobile users has

skyrocketed—the bar for 2020 won't be along this "steady" growth line but more

of a quantum jump.

What's the point? If you are in banking, you better get

really good at delivering mobile banking. It's no longer an option to have a digital platform, it's a requirement—you need to be thinking in terms of kintsugi,

not wires and staples. How do we take a system that used to be largely branch

and ATM-related and move to one that is totally seamless (and beautiful) remotely?

We face a wakeup call, similar to the airline industry—things have changed and

we can choose to move to a better, new solution, or we can still "board from

the front."

Speaking of broken pottery, let us consider the

bond/financial markets.

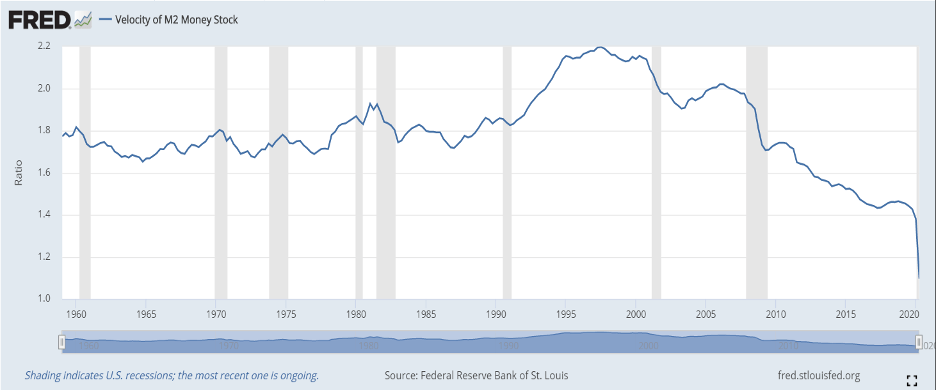

You may know that one of the key statistics that I like to follow

is the Velocity of Money (V). Of the four key macro-economic measures—the

others being Money supply (M), Inflation (P), and GDP (Q)—Velocity is the only one

that cannot be directly observed and measured, but must be derived from the

others: MxV= PxQ. The latest calculation is not encouraging.

The latest reading is 1.097. This is the lowest point ever recorded by the Fed. Money is not turning over.I

think we all know that there are many broken systems right now due to this

terrible scourge, but from a financial perspective, this one actually scares

the crap out of me. We know that the money supply is skyrocketing, so the M x V

half of the equation is being held down only by the fall in V. We also know

that the Q (GDP) is dropping fairly dramatically. That leaves P (inflation) on

a hair-trigger. If the equation is correct—as it has been for centuries—then

any pick-up in velocity means that the prices need to go up, maybe a lot. We

are already seeing this in commodity prices. Yes, this is partially due to

dollar weakness, but I fear that it may be more systemic. Never forget the

stagflation of the 1970s. That is the last time we have had a similar evil

brew of statistics. Let's hope this does not happen a second time around, but let's

not ignore the possibility, either.

We know we each have a broken vessel, and somehow or

another, it will be repaired. The question we need to ask ourselves as business

owners, bankers, or entrepreneurs is whether we send back a business stitched together

with cheap metal thread, or create, with really cool gold lacquer, something

better and beautiful. The path of least resistance is the former. Take care not

to take it.

Final, final thought: jalapeno-cheddar bagel with salsa cream cheese. Give it a try.