It doesn't seem that long ago, but it has been nearly 30 years since my days of trading on the floor of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange.

What a rush. I traded in the British Pound pit, and we kicked off every day at 7:20 AM. If you weren't pit-side by 6:45 you would not get your spot. By 2:00p when that exchange closed, I would normally be drenched in sweat. I can tell you that in that pit, you really got to know your neighbor. We were literally squeezed together all day. It was an awesome experience that I will never forget.

I also worked for a smallish company called Timber Hill. It

was owned and operated by Thomas Petterffy (who eventually founded Interactive

Brokers). We actually had touch sensitive screens in the early 1990's where we

could enter our trades. That was not a common technology in those days. Mr.

Petterffy had established a code of colors-for-numbers that could be displayed

on a computer screen that we could see from quite a distance, which helped a

lot since there was no way to squeeze a computer in with us in that pit. To

this day I remember the code: 1 = Pink, 2 = Light Blue, 3 = Dark Blue, 4 =

White, 5 = Red, 6 = Brown, 7 = Green, 8 = Gray, 9 = Yellow and 0 = Black. Our

system was way ahead of its time. I could see the screen and our pricing levels

from at least 50 meters. Once a trade was executed, I would hand-signal my

clerk and he would enter the trade into that computer, updating our risk

position across all exchanges instantly on all screens in our company platform.

In this job I was also taught about options and thought

about them all day. This turned out to be a critically important body of

knowledge for the rest of my nearly 30 years in the financial industries.

One of the most important lessons in this curriculum was defining

various option strategies. Perhaps most important of these are the definitions

of call and put options. A call option is "the right, but not the obligation,

to purchase an underlying security at a future time and price." A put

option is "the right, but not the obligation, to sell an underlying

security at a future time and price."

These were the basics for me, every day in the pit. Those,

and hedging. If I bought call options, I had to sell some futures, to hedge

myself. If I bought put options, I had to buy futures to hedge myself. Every

trade had an offset based upon the Black-Scholes model. I'm oversimplifying,

but for every trade there was always an offset. And of course, there were often

more complicated trades, requiring more complicated hedges.

One of my most poignant memories is of a day when I made one of my largest (by volume) trades.

I sold a large amount of way out-of-the-money puts on the British Pound. I felt like I had made a good trade and was basking in my "glory" when the phone at our desk rang, and the clerk started frantically waving over to me. When I got to the phone, it was Mr. Petterffy on the line, and he had a very terse four-word message for me: "Don't Sell Cheap Options!" Then he hung up.

You see, the problem with selling cheap options—be they

calls or puts—is that they can become very hard to hedge…especially if the

market is moving quickly. By selling all of these "cheap" puts I was putting

our firm in a highly risky situation without much reward. Let me be clear what

he meant by cheap. He didn't mean that I had sold them at a slightly lower

price than the next guy would have; that is the definition of trading, the

lowest price sells, and the highest price buys. He meant that on that day, what

the market was bidding for those puts was not sufficient for the risk to us of

selling them. I don't think he would have been happier if I had eked out a

slightly higher price.

It felt great to make the "big trade," but, I was putting us

in a high-risk situation. We can talk about Delta and Gamma another day, but

suffice it to say, he was not pleased. A valuable lesson for me.

When I eventually made the career move into the banking

industry, I assumed that my option experience would be important to me in

helping me keep up with what I expected to be a great deal of practical wisdom

around options. What I found was entirely different.

It turns out that the banking and credit union industries in

the United States are addicted to selling cheap options. Almost

everywhere I look, I see portfolio managers selling options, and almost 100% of

the time it's way below the "correct" price. Let me say this again, by correct price,

I mean a price commensurate with the risk of the option sold, not commensurate

with what everybody else happens to be paying.

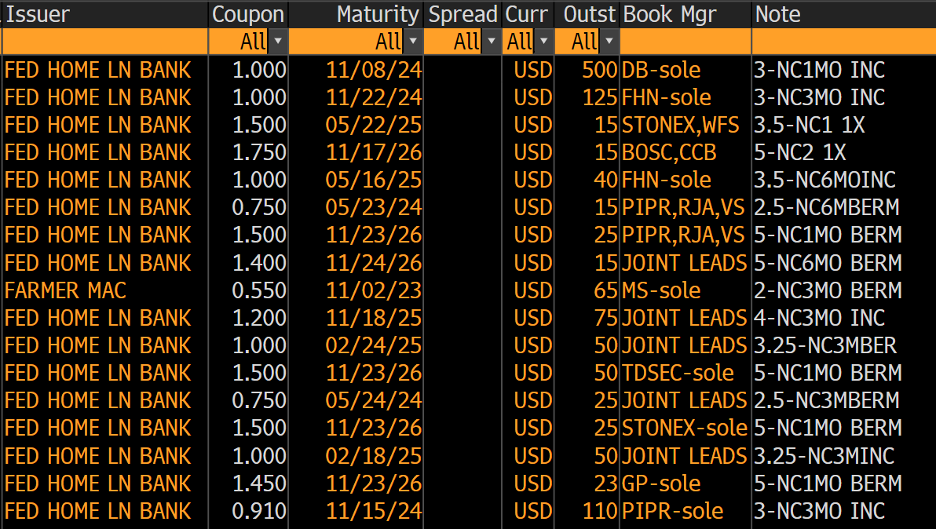

Let us first examine the callable bond market.

All day, every

day, callable bonds are being issued into the marketplace. A huge percentage of

these offerings are gobbled up by community financial institutions. How do I know this? I can follow it on

Bloomberg, among other sources, using their NIM2 monitor which follows agency

issuance every day. Here is today's sample:

This updates throughout the day, and it shows us that the

Federal Home Loan Bank (among others) is constantly issuing debt which includes

a call option. 99.9% of the time, the FHLB is buying the embedded call option, and

the purchaser is selling the embedded call option. If you look in the far-right

column of this image, you will see that nearly all the call options are less

than 6 months in duration (NC3MO, for example, means "callable any time after

three months"). Once the call option goes "live", the issuer can call back the

bond at a price of par whenever it wants… no matter how much that cash flow

stream ought to be worth without the call.

Why would anyone sell all the possible upside in a security

they are purchasing? Mr. Petterffy would

not be happy! Why? It's hinted in my title: an insatiable appetite for "higher

yield." Is this appetite rational, or a little irrational?

If you look carefully above, many of the coupons that the

agencies are issuing are at, or just slightly above, 1.00% (see column 2). It's

a magic number apparently, because very few issues are at 0.95%. That's no accident. It is an illusion that

appeals to our emotional decision-making. "1.00% is to 0.95%" is a much bigger

deal to many decision-makers than "0.95% is to 0.90%", and issuers know this.

So maybe a little bit irrational.

Leaving aside the "magic number" component, picking up only

5 or 10 bps in exchange for providing the issuer with a call option makes no

sense. And yet investors do exactly that every day.

Think about it: if after purchase, interest rates were to fall, the bond should become more valuable with its higher-than market fixed coupon. But it won't, because the option will be exercised, forcing the owner of the security to sell their security at $100 (actually, this will all be done on their behalf!), leaving them with the proceeds to invest at the new, lower coupon rates.

Well, at least they got 5-10 bps extra, right? Um, no. If

you have the higher rate for only three months, you do not get 5 or 10bps, you

get 1.7 or 3.3 bps.

Meanwhile, the CFOs of the agencies can hardly believe their

luck, because they are able to issue fairly long-term liabilities that they can

reset at lower and lower rates if they should fall but are safely locked in should

they rise. It is truly head-I-win, tails-you-lose for the issuer.

Now, "Dangerous Reach for Yield" behaviors go well beyond

simply selling cheap embedded options in the process of purchasing bonds. In

recent posts, we have discussed very troubling trends in the world of credit

risk. These trends have repeated themselves several times over the past thirty

years of my experience, and I've never seen it end well. As one of my mentors

once told me, "Interest rate risk will nibble your fingers, but credit risk

will tear your arm off." Don't forget that. We will cover credit risk in future

posts, to be sure.

Remember: Count the money, across a variety of interest rate scenarios, over time, and you will have a much better handle on the truth of the decision.

Final, final thought: I'm currently obsessed with peanut butter

M&M's. I think they might be my favorite Halloween treat, but I'm willing

to hear other opinions. LMK.

Fill out the form below to subscribe to my weekly blog.

The information, analysis, guidance and opinions expressed herein are for general and educational purposes only and are not intended to constitute legal, tax, securities or investment advice or a recommended course of action in any given situation. Information obtained from third party resources are believed to be reliable but not guaranteed. All opinions and views constitute our judgments as of the date of writing and are subject to change at any time without notice.